Naming, shaming, and demolishing their platforms: Social media is winning the war with the violent far right

As violent right-wing individuals and groups have increasingly used the Internet to spew their rhetorical bile, oftentimes emboldened by the vitriolic, fascistic utterances and behavior of failed university owner Donald J. Trump, several social, political, and media pundits have remained strongly opposed to “doxing” — the practice of exposing a (usually but not always anonymous) social media user’s identity and contact information — arguing that it is at very least an intrusion on privacy.

Similarly, campaigns to “deplatform” voices that fuel racial, religious, political, and social brutality have faced similar criticism.

Similarly, campaigns to “deplatform” voices that fuel racial, religious, political, and social brutality have faced similar criticism.

But the fact is that these tactics work as part of a broader. stochastic strategy to expose, delegitimize, and even force legal action against vicious and even homicide-coddling far right extremists.

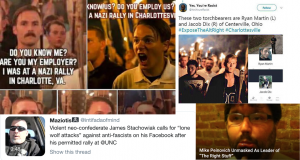

In some cases, the efforts not only expose the names of new-wave Nazis, but do so hilariously:

The website went live last Monday, taking aim at “problem Germans.”

“Wanted: Where do these idiots work?” the prompt asked. It directed visitors to images of some of the 7,000 people that the website’s sponsor, the German art collective called the Center for Political Beauty, or “ZPS” in German, said took part in a right-wing mob that seized the streets of Chemnitz this summer.

The Web page asked members of the public to identify neo-Nazis at the protests, which turned the former industrial hub of prewar eastern Germany into a cauldron of xenophobic anger in the heart of Saxony, where the nationalist, anti-immigrant Alternative for Germany, or AfD, won more than a quarter of votes in 2017, making it the strongest party in the state on Germany’s far-eastern flank.

…

The street scenes made Philipp Ruch, the founder and artistic director of ZPS, wonder: “Who are these guys?”

His question was soon answered by the “guys” themselves. They got trapped in a “honey pot” set up by the left-wing art group, as they searched their own names and the names of associates once ZPS put the results of its initial sleuthing online for all to see.

Read how ZPS ingeniously pulled off arguably the largest mass doxing here. They are, as The Guardian‘s Jason Wilson points out, not alone by any means.

This year, antifascists have used photographs of street events like Unite the Right in Charlottesville, revelations from compromised chat servers, and the kinds of extensive trails that all of us leave online in order to connect far right violence with the real names of the people who perpetrate it.

Doxxing campaigns – aimed at Proud Boys, neonazis, and individuals who attended events like Charlottesville – have fed into reporting on these movements, and even, eventually, into prosecutions.

The fate of the Southern Californian group RAM is instructive here. The group’s activities and identities were first highlighted by a Californian antifascist group. They then became the focus of reporting by ProPublica and PBS. Following this, authorities finally moved against the group for its activities in Charlottesville.

…

A second strand of activism – which has taken myriad forms – is that which seeks to deny speaking platforms to the far right. Some no -platforming has gone through conventional channels, and has been carried out by people who do not even identify as antifascist.

Nyadol Nyuon, a lawyer in Melbourne, led a petition campaign earlier this year aimed at convincing Australia’s immigration minister to deny Gavin McInnes a visa for a planned speaking tour.

…

No-platforming has also happened on social, and even broadcast media.

In the last year alone, major platforms have acted to limit the reach of conspiracy theorist Alex Jones, who had previously been using the social media services to bring more eyeballs to his mixture of toxic myth making and snake oil sprucing.

McInnes and the Proud Boys were also banned from almost every major social media platform following their involvement in several violent incidents in American cities.

There are indications that online no-platforming works. After Milo Yiannopoulos was deplatformed on Twitter, he was made persona non grata but the very conservative movement he had been courting. Now he’s broke.

It is astonishing that violent neo-fascists have been so blinded by their hubris that they did not see smarter and better organized groups kicking over their rocks and exposing their members by name to sunshine — and public excoriation.

Our editorial view is that despite reasoned arguments founded on the questionable ethics of doxing, violent brownshirts and their enablers and fellow travelers who are hiding behind anonymity need to be named and shamed.